Why Rappers Started Running Their Own Music Festivals

Each year, more hip-hop artists start festivals, but each festival needs to stand out in an increasingly crowded market.

Travis Scott (via Shutterstock)

Join the music execs that are signed up for the Trapital newsletter!

Join the music execs that are signed up for the Trapital newsletter!

Last week, Travis Scott announced he is starting the Astroworld Music Festival in Houston this November. The 26-year old rapper joins J. Cole and others who are starting their own festivals this year. As music festival culture has exploded—there are now over 800 in America—hip-hop artists wanted more skin in the game. These artists now earn money from ticket sales, sponsorship, and concessions. If the festival is done right, it’s a lucrative opportunity.

Chance The Rapper’s Magnificent Coloring Day festival in Chicago broke an attendance record at U.S. Cellular Field. Jay Z’s Made in America Festival was one of the 15 highest-grossing festivals in the world last year. Tyler, The Creator's upcoming Camp Flog Gnaw Carnival sold out within hours. And since 2015, the percentage of hip-hop acts at Coachella has doubled. Hip-hop is now a cornerstone in music festival culture.

Festivals are high-risk opportunities though. Land costs, rental fees, logistics, security, and artist fees are not cheap. New festivals can take several years to break even. High ticket sales and sponsorship dollars are essential. Event planning for multi-day festivals requires a dedicated team putting in long hours, so opportunity cost is high.

Travis Scott, J. Cole and other first-time festival organizers can avoid these struggles with an intentional plan. Festivals need to offer a unique experience that is true to the artists running them. Both fans and sponsors reward authenticity.

It’s more lucrative for Travis Scott to sponsor a brand at his own festival than someone else’s.

The commodity market

Each year, a bunch of thinkpieces are written about how there are too many music festivals. Most of these critiques stem from a lack of differentiation. Back in the 90s and 2000s, most popular festivals had a unique identity: Coachella was for hipsters, and Bonaroo was jam bands and folk rock music. A festival’s identity used to set the tone for the lineup. But today’s popular festivals conform to landing the biggest artists possible to sell tickets. Since more artists are doing “festival runs” each year, these events quickly became a commodity.

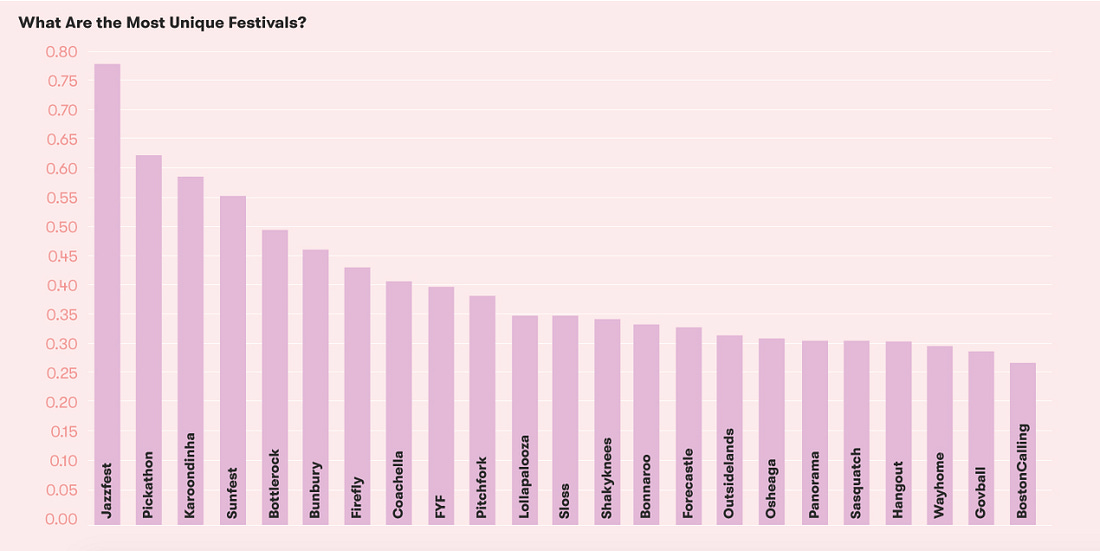

Here’s a chart from Pitchfork that measured the uniqueness of festival lineups in 2017. The higher the number, the more unique the festival was:

From Pitchfork: The uniqueness score is essentially the reciprocal of the average number of festivals that will be played by a given festival’s lineup—the more unique the lineup, the higher the score.

From Pitchfork: The uniqueness score is essentially the reciprocal of the average number of festivals that will be played by a given festival’s lineup—the more unique the lineup, the higher the score.

Bonaroo was once a beacon in festival culture, but it’s now one of the least unique festivals. In 2016, attendance dropped 46% from it’s all-time high. The festival has since struggled to maintain profitability. This year, Eminem was a headliner at Bonaroo. He also headlined this year at Boston Calling—the most basic music festival on the chart above. According to an Eventbrite survey, 1/3 of festival organizers said they struggled to stand out to sponsors. The best way to stand out is to cater to a specific audience.

A focus on niche opportunities

Travis Scott has yet to announce the Astroworld Festival lineup, but he can separate from the pack by tapping into Houston’s deep rap scene. Throughout his top-selling album Astroworld, Young La Flame paid homage to Swishahouse rappers Slim Thug, Mike Jones, and Paul Wall. Travis should get these local legends to join him on stage.

This would help Astroworld stand out from Houston’s other music festival, In Bloom. This year, In Bloom’s lineup included Beck, Lil Uzi Vert, Incubus, 21 Savage, and T-Pain. It’s a star-studded lineup, but could easily be the lineup for Outside Lands or Lollapalooza as well.

A regionally-focused niche festival has a comparative advantage too. In 2018, Lil’ Uzi Vert has a higher artist booking cost than any Swishahouse rapper does. But the willingness to pay to see the “XO TOUR Llif3” rapper is higher in his hometown of Philadelphia than it is in Houston or any other city in the South. The same is true for Swishahouse. Paul Wall and Mike Jones will be most popular in H-Town—making the return on their booking costs greatest in Houston. It’s also cheaper and easier to book local acts, since their travel requests and riders are less complicated to manage than out-of-town acts.

An artist-run niche festival is a great way for the organizer’s label to put its other artists on the map too. Drake’s OVO Fest always features artists that are signed to OVO Sound. J. Cole will likely do the same with the upcoming Dreamville Fest. There’s also a cost advantage. “Artist-backed events have the advantage with lower talent costs, since they don’t necessarily have to bid for as many bigger headliners,” said writer Dave Brooks in Billboard.

Sponsorship dollars can be higher at artist-run festivals too. Here’s another excerpt from Billboard on this topic:

“Not only do [artist curated] festivals get brands closer to the artist in charge, they also include increasingly valuable promotion on the act’s social media feeds, which boast far better engagement than a traditional festival’s social accounts.”

It’s more lucrative for Travis Scott to sponsor a brand at his own festival than someone else’s. Travis is also more likely to ask his partner Kylie Jenner to post about the festival to her 113 million Instagram followers and include a sponsoring brand’s logo (but don’t tell Nicki Minaj).

Who else should start a festival?

Travis Scott has all the tools to make Astroworld a success. Other artists can do the same for their respective niches and regions.

Wiz Khalifa and Mac Miller have repped Pittsburgh proudly for years. The two rappers went on tour together in 2012. Both artists also released new albums this summer and are touring separately this fall. Once their tours are over, they can collaborate once again to create a smaller scale hip-hop festival in the Steel City.

Pittsburgh does not have a major music festival. The next closest one is over 150 miles away (which addresses the exclusive radius clauses that prevent artists from performing at nearby shows in the same time frame). This “WizMacFest” would draw midwest rap fans from Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Columbus metro areas. There are several up-and-coming Pittsburgh rappers that could join Wiz and Mac Miller on stage. This festival would be cheaper than others, since land and labor costs in Pittsburgh are cheaper than other cities.

Another good, yet overdue opportunity is to bring women in hip-hop together. Queen Latifah ran a women-centric hip-hop festival in 2005 and 2006, but that was before festivals blew up. Last year, the Rolling Loud Festival took heat for only having three women in its 57-act hip-hop lineup. Latifah mentioned bringing the “Black Lilith Fair” back a few years ago. The timing now is better than ever.

Earlier this year, the “Queens of Hip-Hop” concert brought together legacy acts like MC Lyte, Rah Digga, and Eve in Atlanta. North Carolina rapper Rapsody put out one of the most critically-acclaimed rap albums last year with Laila’s Wisdom. And Cardi B is one of the most commercially successful rappers this year. It’s a shame that there have not been more recent attempts. According to DJBooth, there’s a disconnect between fans and organizers:

“I think that if it were up to people like us who love the music and want to see a diverse representation of the culture, then you’d absolutely see lineups that invite women outside of their press date or when they’ve just put something out that’s poppin.”

It’s no surprise that fans want diverse lineups and are willing to pay for it.

Hip-hop’s rise in music festivals is remarkable. It was only nineteen years ago that Damon Dash and Jay Z had to hire Nation of Islam security at concerts to prove that a small group of rappers can be trusted to perform in basketball arenas. And today, Travis Scott—who’s known for jumping off roofs and stages at concerts—is running his own festival. What a time.

Change was coming though. Hip-hop artists were not going to sit around and let traditional festival operators earn all the top line revenue—especially when artists themselves have the potential run more profitable events. It’s in the hustler’s mentality to move up the value chain.

Trapital is written by Dan Runcie. Contact me at dan@danruncie.com