Why Streaming Exclusives Are Here to Stay

Frank Ocean, Beyoncé, and others helped push forward the highly-debated album release strategy that continues to evolve each year.

Frank Ocean (via Shutterstock)

After three long years, Lemonade is now available everywhere. Beyoncé’s tell-all project was one of the last albums standing from the brief surge of exclusive releases. In hindsight, those years seem far removed from today’s industry. Drake’s Views —an initial Apple Music exclusive—feels like it dropped five years ago! The streaming era has seemingly evolved, but each platform is still in a constant quest to differentiate.

The peak-exclusive era was wild. Those lucrative deals made artists richer and streaming services bigger. But the era was also full of disastrous rollouts, okey-dokes, scandals, and everything in-between. Universal, Spotify, and many others had chastised the practice to a temporary hold.

But despite their strong stance, exclusive content is still here. It’s taken a different form. Each digital streaming provider has exclusive music videos and other bonuses to differentiate. Competition is fierce. As artists gain more power, it’s unlikely that the record label’s push against exclusive albums will still hold weight.

Exclusivity still makes sense for some artists

Most artists need to decide whether they want to maximize revenue or audience. Both can be achieved, but one is usually prioritized and the other follows.

For those who focus on revenue, exclusivity can often extract the most value. Exclusivity is not just the $20 million deals that Apple Music made with Drake, Taylor Swift, and others. Artists can also exclusively distribute music to their top fans who will knowingly spend more money. Here’s what I wrote earlier this month in How Nipsey Hussle’s Marathon Can Continue:

[Nipsey Hussle] used a windowing tactic to maximize revenue from loyal fans. After selling past mixtapes for $100 and $1,000, he knew his day-ones value exclusivity and pay top dollar for it (even though the project would be widely available soon after). The high sticker price was both a marketing tactic and a price discrimination move. Every business should want to maximize each customer’s willingness to pay. When die-hard fans spend the same money on a product that a casual fan does several months later, money is left on the table.

It’s impossible for an artist to maximize a fan’s willingness to pay on Spotify alone. Spotify doesn’t tell artists who their fans are! Listeners cannot be segmented on the platform.

On streaming services, each artist is bundled into an all-you-can-consume package. Sure, superfans generate more streams than anyone, but those streams still yield (fractional) pennies on the dollar. High streaming numbers—even from diehard fans— cannot match the revenue that the fan’s core audience is willing to pay outside the platform.

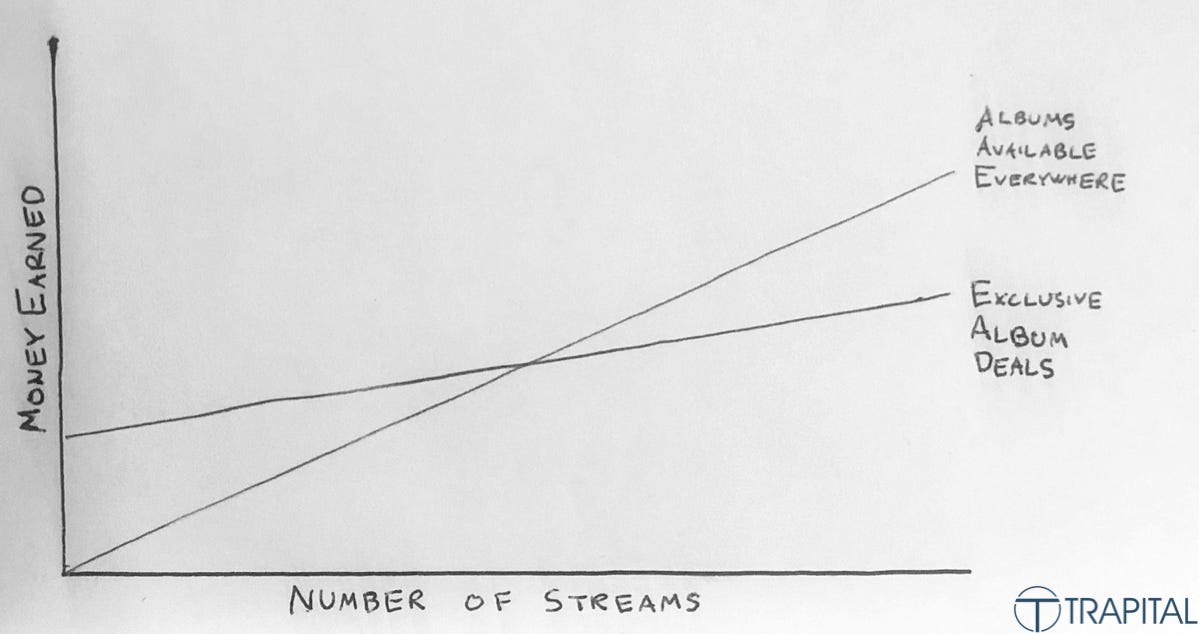

Alternatively, widely distributed releases make sense for artists with massive fanbases and promotional support across streaming services. At that point, ubiquitous access is more advantageous than exclusivity. There’s a natural break-even point:

This chart can be exercised more by indie artists. They own their content. But it’s less actionable for those artists signed to a label. For the labels, the music (and not necessarily the artist’s brand) is the owned asset. The more that music is accessible across all platforms, the better. Labels also maintain power by not relying on a sole streaming service to distribute music to consumers.

Power dynamics are changing

In August 2016, the labels had a brief panic moment. Apple Music exclusively released Frank Ocean’s visual album Endless to fulfill his contract with Def Jam. The next day, Apple Music and the “Pyramids” singer dropped his real album, Blonde, on Ocean’s independent label. It was a gut punch to Def Jam, Universal, and the industry. If Frank can bypass the labels and partner with streaming services directly, what stops others from doing the same?

Universal’s CEO Lucian Grainge put a stake in the ground and said that the label would no longer do exclusives with a streaming service. Spotify has also been a loud voice against exclusives. Here’s Troy Carter, Spotify’s global head of creator services, in a 2017 interview with Variety:

“Exclusive audio content, specifically with albums, is not within our playbook. I think people have learned over the last six months that it’s bad for the music industry, it’s not that great for artists because they can’t reach the widest possible audience, and it’s terrible for consumers. If you wake up in the morning and your favorite artist isn’t on the service that you’re paying ten dollars a month for, sooner or later you lose faith in the subscription model.”

Carter’s stance is understandable, but Spotify’s moves in podcasting have challenged this notion.

When I go to the barbershop, The Joe Budden Podcast is usually playing on YouTube. But now we gotta wait two days to watch Budden’s latest hot take on mumble rap. Why? Because each episode is a Spotify exclusive for the first 48 hours. It makes sense for Spotify, but it contradicts the position once taken. It also delays the timely barbershop debates that ensue, which is a shame!

For Spotify, the difference between albums and podcasts is the power that content owners have. The podcast industry is fragmented. Major podcast studios are far less powerful than any of the Big 3 record labels. It’s less controversial (and cheaper) for Spotify to produce exclusive podcasts. But if power shifts over time in the music industry, Spotify’s podcast strategy can be a sign for what the streaming services ultimately wish can happen in music.

Streaming services still need to differentiate

At the moment, streaming competition is focused on subscriber growth. Apple Music has proudly eclipsed Spotify in paid U.S. subscribers, but Spotify still holds the global crown. Spotify will make it known when it surpasses 100 million paid subscribers, but that massive subscriber base comes at a cost.

Earlier this year, Music Business Worldwide’s Tim Ingham reported in Rolling Stone that the average Spotify monthly subscriber pays a mere $5.50. That number is driven by substantial promotional offers, student discounts, bundles, and family plans. That number will go down further as both Spotify (and Apple Music) continue expanding in emerging markets. In India, monthly subscriptions for each service is under $2.

If the streaming services can’t extract more value from these newly acquired customers (which might happen with students, but not the other groups), they will have to compete in other ways. Spotify’s podcast strategy is an attempt to differentiate with less expensive content, but CEO Daniel Ek has said that podcasting will likely represent a 20% mix of its audio listening. All signs point back to DSPs competing more heavily on albums, the core part of their business.

If today’s most streamed artists all became independent —a drastic change, but not unrealistic given the environment— labels would lose tremendous power. At that point, it’s unlikely that Spotify, Apple Music, or any other streaming service will be as deferential as they are today about the label’s preference against exclusive albums.

Artists are in more control than before. The current hip-hop wave is conditioned to bypass labels and control their own destiny. This generation will inevitably deal more directly with streaming services.

If Spotify starts offering rappers mixed deals for a two-week album exclusive and a 10-part behind-the-scenes podcast that documents the album’s creation — which more hip-hop artists should start doing —don’t be surprised. That reality is closer than we think.

By then, Drake’s Views will feel like a historic artifact.

If you enjoyed this story, forward to a friend and tell them to sign up for the newsletter!

Trapital is written by Dan Runcie. Contact me at dan@danruncie.com.

Most-popular Trapital stories of 2019: